Reusability in Infrastructure as Code

This article reflects on the benefits and avoidable pitfalls of designing reusable Infrastructure as Code modules written in Terraform. I will share some concepts and code as well as a simple framework to guide coding. It is written through the lens of about 30 years immersion in professional software development, engineering, architecture, and management, using lessons from the past to solve current problems. Chief among them is monolothic code that evolves rather than is designed, and becomes all-encompassing.

Those 30 years have witnessed many failed attempts to create reusable code. Those failures often occurred due to complexity of code (hard to understand how to reuse it or how to maintain it), lack of confidence due to code quality, and adaptability to new requirements. We see those in large-scale infrastructure efforts currently, but can minimize those issues.

The key recommendation of this post is to use the Terraform module construct intentionally to define use cases for it, which guides engineers on what goes into their code. A module should be easily classified as either a hardened module or a deployment pattern, but not both. A single module should not play both roles. This article defines both archetypes.

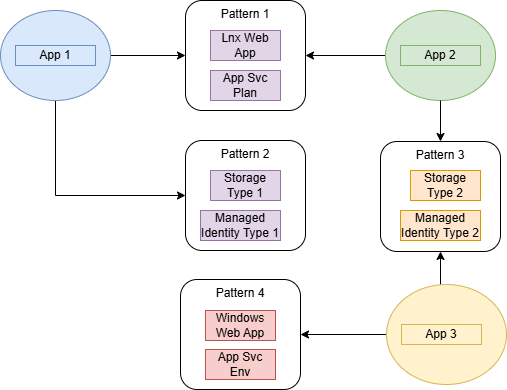

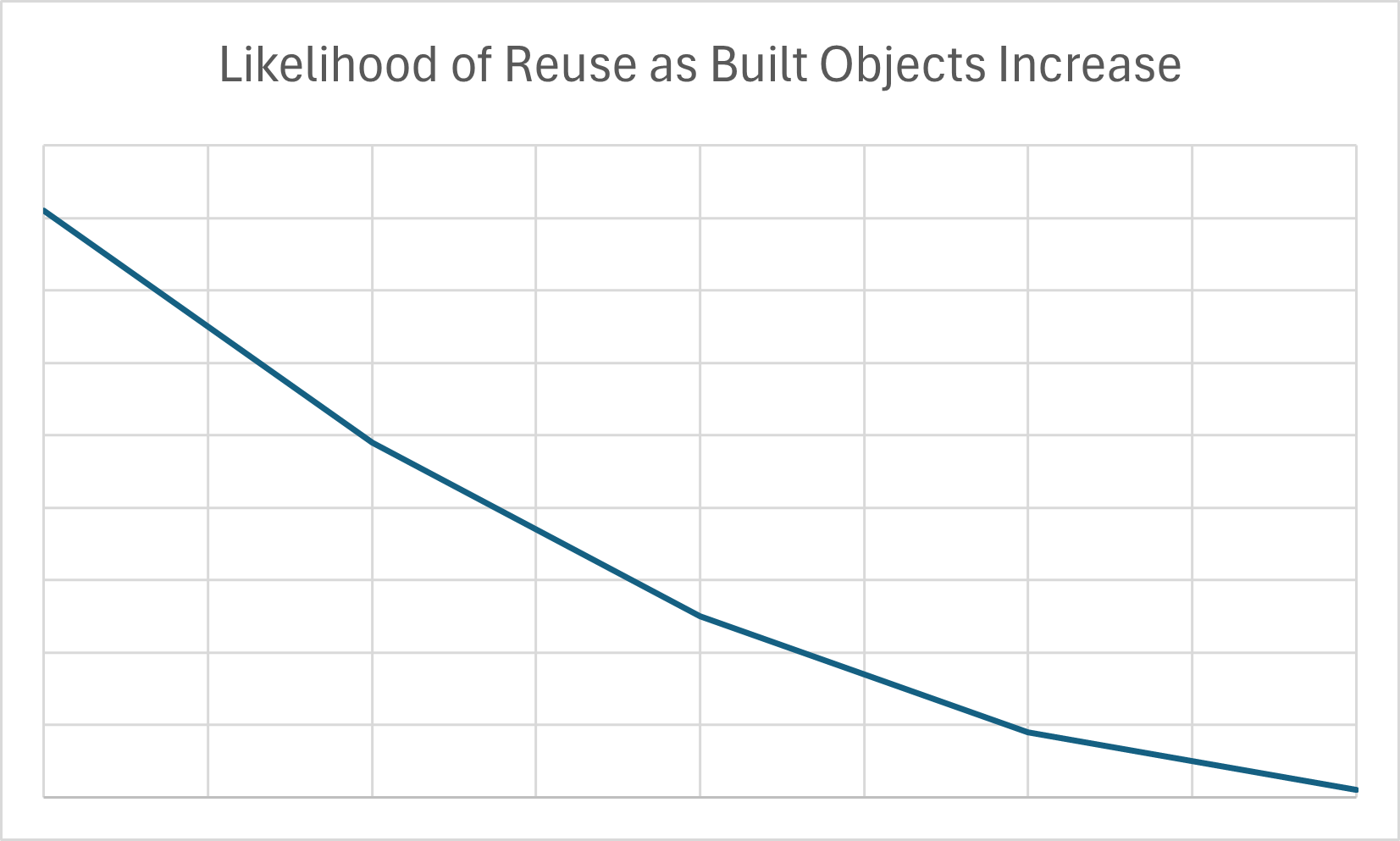

When modules are not written with these two classifications in mind reuse is reduced, because engineers will not consistently decide to include Terraform resources. See the chart that illustrates the relationship between how many components are in a module versus likelihood of reuse, based on years of observation.

Why Reusability is Important

The challenges in reuse start in getting configurations just so for your unique infrastructure environment, where security policies, financial priorities, skill sets, and volume of work are different between every company. And then are compounded when clear guidelines don’t exist.

We want to write reusable Terraform in cases where it is particularly tricky or errors can occur. These may include incorporating corporate security policies, FinOps requirements, or other Cloud Engineering best practices. Getting a library of these helps an organization more easily support infrastructure management.

Let’s address the kinds of things that go into such a library to maximize reuse.

Composable Architecture

The parallel to the “composability” attribute of SOA and microservices design should be drawn. This concept helped developers avoid fragile monolithic services and build for their businesses faster. A hardened module supports a composable architecture by being atomic in nature while the deployment pattern serves as the composer, pulling together the atomic units to solve business problems.

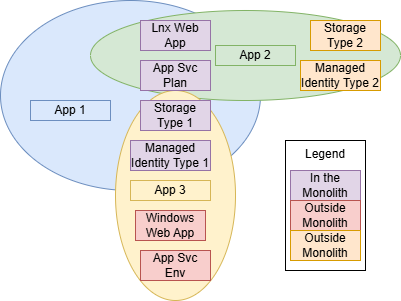

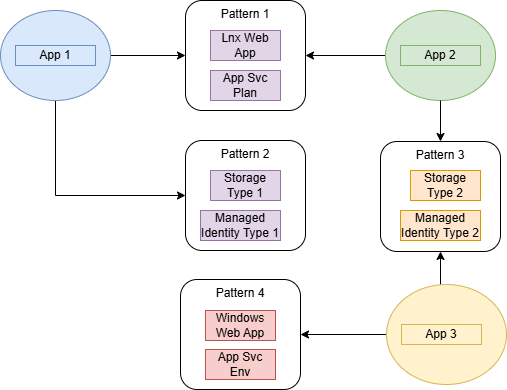

Compare below the cases of a monolith and a composite structure. Note how the monolith suits the needs of one application. The others might choose to use it but likely will not, because it creates resources that they don’t need. And then notice how the composite provides smaller, less complex modules that are easier to code and test.

Monoliths Detract from Reusability

A Composable Architecture Promotes Quality Reuse

Maintainability is Longevity

With reusability we need to consider maintainability and code stability. Maintainability is how we make sure that others understand what we did, and that we did it consistently. Building a lot of things in one code package is complex and can be hard to follow. Complex code is fragile; it breaks easily!

Stability Breeds Confidence

Stability means that when we want to use code, there is a version of it that is known to be well-tested and functioning. Without these, your code will be abandoned because it is not clear how to support it or shunned due to low quality.

The Framework: Hardened Modules and Deployment Patterns

We can differentiate two main types of Terraform modules: hardened modules and implementation patterns. A hardened module is focused on a small set of resources that are configured to a set of non-functional requirements, while an implementation pattern is a composition of multiple resources that are commonly implemented as wired together to achieve a certain platform model.

Without this differentiation, it seems like a judgement call as to when to add on to the module and when to create a new one.

Code Examples

An example of hardened modules would be a Linux Web App in Azure. It needs to be configured with encryption, a range of allowed capacities for cost reasonableness, and authentication. But also, to actually be useful, that web app needs storage and a managed identity (service principal in Azure lingo) to communicate with that storage.

So here are two scenarios - one that builds the monolith, an opinionated construct of all the things I need for a web app, versus independent components. These demonstrate how, without planning, that module becomes an complex, unstable, unmaintainable, and fragile burden which won’t be reused.

The Monolith

Here’s all the things we need for the web app, so let’s roll them together. Then, when someone else needs a web app, they can reuse it? We’ll see! Let’s leave out the network considerations as we can illustrate the point without adding in that volume of items.

- An instance of a Linux Web App, tuned to my organization’s security policies

- An application service plan to provide the compute resources for the web app

- Storage for the web app, tuned to my organization’s security policies

- Managed identity (i.e. what Azure calls a service principal) assigned to the web app

- Multiple privileges for that managed identity to manage storage for the web app

- Required diagnostic settings for the web app (In Azure these can be discretely tuned as separate Terraform objects)

- Required diagnostic settings for storage

Here’s what that code would look like. You would use it by saving in its own folder in your project or, better yet, in its own repo. It’s an incomplete example so you can’t use it directly, sorry.

resource "azurerm_resource_group" "rg" {

name = "example-resources"

location = "West Europe"

}

resource "azurerm_user_assigned_identity" "uai" {

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

name = "db-uai"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

}

resource "azurerm_storage_account" "storage" {

name = "examplesa"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

account_tier = "Standard"

account_replication_type = "LRS"

}

resource "azurerm_monitor_diagnostic_setting" "webapp" {

name = "storagediag"

target_resource_id = azurerm_storage_account.storage.id

log_analytics_workspace_name = "my_law_name" # don't forget to create this resource too!

enabled_log {

category = "AuditEvent"

}

metric {

category = "AllMetrics"

}

}

resource "azurerm_role_assignment" "acct_role" {

scope = azurerm_storage_account.storage.id

role_definition_name = "Storage Account Contributor"

principal_id = azurerm_user_assigned_identity.uai.principal_id

}

resource "azurerm_role_assignment" "blob_role" {

scope = azurerm_storage_account.storage.id

role_definition_name = "Storage Blob Contributor"

principal_id = azurerm_user_assigned_identity.uai.principal_id

}

resource "azurerm_service_plan" "plan" {

name = "app-plan"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

os_type = "Linux"

sku_name = "P1v2"

}

resource "azurerm_linux_web_app" "app" {

name = "myapp"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_service_plan.plan.location

service_plan_id = azurerm_service_plan.plan.id

storage_account {

account_name = azurerm_storage_account.storage.name

access_key = azurerm_storage_account.storage.primary_access_key

}

identity {

type = "UserAssigned"

identity_ids = [azurerm_user_assigned_identity.uai.principal_id]

}

site_config {}

}

resource "azurerm_monitor_diagnostic_setting" "webapp" {

name = "webappdiag"

target_resource_id = azurerm_linux_web_app.app.id

log_analytics_workspace_name = "my_law_name" # don't forget to create this resource too!

enabled_log {

category = "AuditEvent"

}

metric {

category = "AllMetrics"

}

}

Save it in its own folder called webapp_module. Parameterize what you’d like. To implement, reference it using syntax like this.

module "app" {

source = "webapp_module/"

... params ...

}

Re-use of the Monolith

Our monolith is a thorough and complete solution for a very specific bundling of a Linux Function App with the resources it requires: a particular kind of storage, a single managed identity, and a single way to set up diagnostics. In other words, we have just provided a hardened implementation pattern, in the form of a single body of complex code. If requirements are exactly all true for the next project, we’ll get reuse out of the monolith.

But very likely there are other outcomes like the following that mean you can’t use that monolith.

- The next project uses a Windows Web App instead of a Linux Function App, so you can’t reuse the storage, identity or settings which we configure.

- Another project requires re-use of an existing storage object and managed identity. That same storage is to be accessed directly by another service and the identity is also created and configured to that other service first.

- Another project needs advanced features to plug into an Application Service Environment for hosting which is more expensive than the other projects’, and require an exception to run in your company’s environment.

You might actually get some re-use, and for those instances, wow, it has exactly what they need with no changes. This is one way to build deployment patterns. Hold that thought and let’s come back to deployment patterns.

Hardened Module as Atomic Components

Now let’s take that same list and break it into logical components that are more atomic in nature, meaning they are more likely to be reused but there might be more wiring required to combine them. This set of modules is going to focus on the non-functional requirements more but leave the door open with parameters to wire dependencies.

Here’s the same essential list of needed products, but flipped upside down.

- Not in modules - applications use these definitions as glue which can vary wildly from one project to the next. See the source code below the two modules.

- The managed identity assigned to the database

- the multiple privileges for that managed identity to manage storage for the database

- Module 1 - the Web App

- An instance of the web app, tuned to my organization’s security policies

- Parameters that identify the storage account and the managed identity to use.

- Required diagnostic settings for the web app

variable "storage_name" { type = string }

variable "primary_access_key" { type = string }

variable "principal_id" { type = string }

resource "azurerm_linux_web_app" "app" {

name = "myapp"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_service_plan.plan.location

service_plan_id = azurerm_service_plan.plan.id

storage_account {

account_name = var.storage.name

access_key = var.primary_access_key

}

identity {

type = "UserAssigned"

identity_ids = [var.principal_id]

}

site_config {}

}

resource "azurerm_monitor_diagnostic_setting" "webapp" {

name = "webappdiag"

target_resource_id = azurerm_linux_web_app.app.id

log_analytics_workspace_name = "my_law_name" # don't forget to create this resource too!

enabled_log {

category = "AuditEvent"

}

metric {

category = "AllMetrics"

}

}

- Module 2 - storage

- A storage account

- Required diagnostic settings for storage, tuned to my organization’s security policies

resource "azurerm_storage_account" "storage" {

name = "examplesa"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

account_tier = "Standard"

account_replication_type = "LRS"

}

resource "azurerm_monitor_diagnostic_setting" "webapp" {

name = "storagediag"

target_resource_id = azurerm_storage_account.storage.id

log_analytics_workspace_name = "my_law_name" # don't forget to create this resource too!

enabled_log {

category = "AuditEvent"

}

metric {

category = "AllMetrics"

}

}

- Finally, Glue it all together.

module "my_storage" {

source = "storage/"

... params ...

}

module "my_webapp" {

source = "webapp/"

... params ...

}

resource "azurerm_resource_group" "rg" {

name = "example-resources"

location = "West Europe"

}

resource "azurerm_user_assigned_identity" "uai" {

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

name = "db-uai"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

}

resource "azurerm_role_assignment" "acct_role" {

scope = module.my_storage.id

role_definition_name = "Storage Account Contributor"

principal_id = azurerm_user_assigned_identity.uai.principal_id

}

resource "azurerm_role_assignment" "blob_role" {

scope = module.my_storage.id

role_definition_name = "Storage Blob Contributor"

principal_id = azurerm_user_assigned_identity.uai.principal_id

}

resource "azurerm_service_plan" "plan" {

name = "app-plan"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

os_type = "Linux"

sku_name = "P1v2"

}

Re-use of the Atomic Components

Because we built the modules to include fewer resources, we can compose them differently in an application.

- Project needs Windows Web App instead of Linux Function App - create a new app module, and re-use the rest

- Project needs to re-use storage and identity - well, just re-use it. The application provides the glue in this mod anyways, so it can re-glue in any way it needs.

- Advanced features of an Application Service Environment - you can create a new module for the ASE or provide variables to drive inclusion of those more expensive features. Judgement call.

What you didn’t have to do was vigorously re-test the modules that didn’t change. Those are in a known, good state.

Deployment Patterns

Since our monolith provides a good definition of the needs of a deployment pattern for our MS SQL database, keep that definition in mind. For an alternate approach, take the hardened modules listed above and wire them together in another module. This additional module is our deployment pattern, and it focuses on the composition rather than the detailed requirements. With a pack of these deployment pattern modules, I can quickly spin up resources for a variety of application platforms.

Here’s what that looks like. Save the following in a folder called webapp_pattern.

module "my_storage" {

source = "storage/"

... params ...

}

module "my_webapp" {

source = "webapp/"

... params ...

}

resource "azurerm_role_assignment" "acct_role" {

scope = module.my_storage.id

role_definition_name = "Storage Account Contributor"

principal_id = azurerm_user_assigned_identity.uai.principal_id

}

resource "azurerm_role_assignment" "blob_role" {

scope = module.my_storage.id

role_definition_name = "Storage Blob Contributor"

principal_id = azurerm_user_assigned_identity.uai.principal_id

}

resource "azurerm_service_plan" "plan" {

name = "app-plan"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

os_type = "Linux"

sku_name = "P1v2"

}

Finally, implement that pattern with the below.

resource "azurerm_resource_group" "rg" {

name = "example-resources"

location = "West Europe"

}

resource "azurerm_user_assigned_identity" "uai" {

location = azurerm_resource_group.rg.location

name = "db-uai"

resource_group_name = azurerm_resource_group.rg.name

}

module "my_webapp_pattern" {

source = "webapp_pattern"

... params ...

}

Design for More

You can mix and match your atomic hardened modules to make whatever pattern combinations you need. And since you have coded and tested the hardened modules to requirements already, the level of testing required is much lower. And you can go faster to get through the 392 applications you need to deploy this year.

With abstraction in our thinking about this need, we’ve spent a little more time upfront but will rapidly gain that time back on additional implementations. Design to keep your constraints manageable and build with your focus narrow. You’ll end up with a higher quality solution and be able to reuse code more often.